As CS Analytical is exclusively dedicated to testing supporting the container and package qualification process, one question that we hear daily from clients is: “I have a plastic container. Do I test materials according to USP <661> or to USP <661.1> and <661.2>?” While the question is simple, the actual answer is a bit complicated. As such, CS Analytical is committed to developing a series of educational articles that will help clients understand all aspects of the USP Container Qualification testing requirements and outline some of the considerations for determining the most applicable test method(s) to your specific package system, materials, and use-case. This article will address some of the basic information regarding both the current USP <661> testing requirements in comparison to USP <661.1> Plastic Materials of Construction, thus providing a foundation for understanding the implementation of these qualification test methods. USP <661.2>, which focuses on plastic packaging systems, will be addressed in future articles.

The USP <661> chapter is currently EFFECTIVE and can be used for qualification of your plastic container and package components that are in use and/or are pending use. The USP <661.1> and <661.2> testing requirements do not become effective until December 2025, but EARLY ADOPTION is permissible. Hence, you can choose to bypass the current USP <661> testing and move straight to the USP <661.1> / <661.2> framework for your plastic materials and package systems respectively. This early adoption approach is highly advisable if the following conditions can be met:

- The product that the plastic container system is holding will be on the market for your company past December 2025.

- New, innovative, or package systems with little historical data are being used.

- There is no expected change in the plastic package system for that product. A change could be defined as a new supplier for the plastic container, a change in the resin used to construct your plastic container, or a change in some part or component of the package system and/or drug product.

If you fully expect that on or after December 2025, the current product and package system will be active and marketed by your company, and that the package’s materials of construction are unlikely to change by this time, it makes sense that the new USP <661.1> testing methods be implemented. If the product is going off patent in 2024 and your company is unsure if it will continue to be marketed and sold, it may be ideal to avoid the additional expense of the USP <661.1> methods and stick with the current <661> requirements, with a more comprehensive reconsideration of a USP testing strategy in a few years.

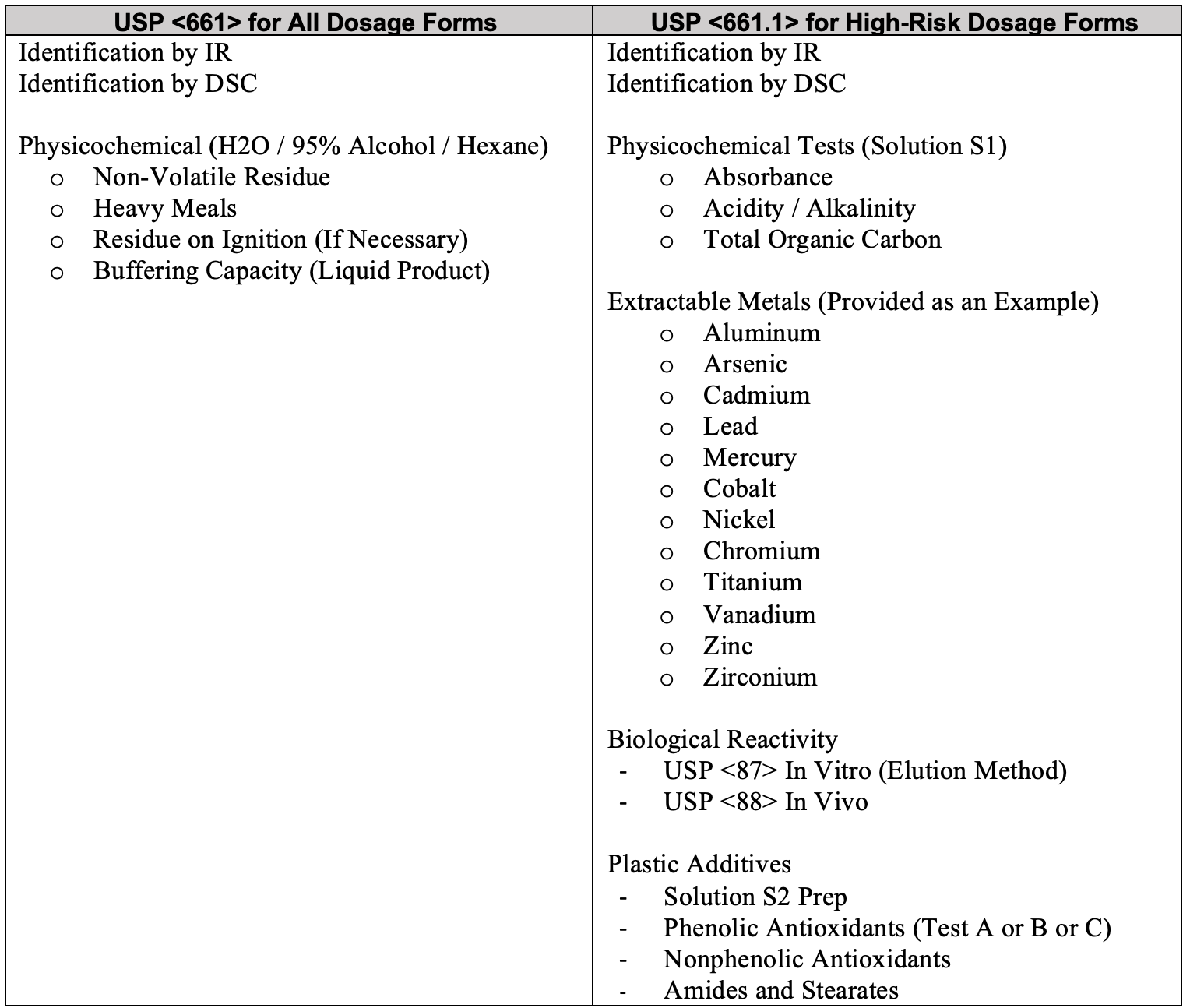

The differences between the current USP <661> methods and the to-be-effective USP <661.1> methods are best described as drastic. This is evident when you look at the scope of plastic types covered, the amount and complexity of testing required, and the overall cost you can expect to pay.

The USP <661> testing outlines methods and specifications for HDPE, LDPE, PP, PET and PETG. The USP <661.1> testing expands the plastic types to include specific test requirements for the following plastic types: Cyclic Olefins, Polyamide 6, Polycarbonate, Polyethylene to include both HDPE and LDPE, PET and PETG, Poly(Ethylene-Vinyl Acetate), Polypropylene, Polyvinyl Chloride, Polyvinyl Chloride Plasticize. The expanded list of plastic types is indicative of how medical product package systems have evolved, becoming more innovative and complex over the past decade. The standard large molecule pill in a white HPDE bottle is becoming the exception versus the norm in today’s drug product market. Biologically-based drugs and machine technology compounds are requiring more unique and complex package systems to ensure their safe and effective delivery to the end user.

The cost perspective of USP <661> and USP <661.1> tends to cause a fair amount of “sticker shock” when formal quotes are provided. To get a basic understanding of the expense difference, it is best to start by looking at the basic list of testing required for a common plastic sample under each general chapter.

Based upon the testing requirements listed, and the associated time and cost of executing the tests, a client is easily looking at a cost difference in the magnitude of 15x the expense for USP <661.1> testing in comparison to the current USP <661> testing for the same sample type. As visible in this test list, the USP <661.1> methods are more extensive, using more complex analytical techniques and instrumentation, which inherently means they are more expensive. The total laboratory time, the amount and extent of supplies, reagents and chemicals and the type of laboratory instrumentation needed for USP <661.1> testing far exceeds the needs of the current <661> testing. While we all agree that cost should not be a critical factor in the development of a drug product that may save lives, in reality, we know that from a business perspective, testing regimes must balance science, safety, risk, and of course, budget. Cost should certainly be a consideration used when evaluated in conjunction with your product’s life cycle stage. As noted, if it is expected that the product in its current form and package system will not be viable for your company beyond December 2025, then the added expense that USP <661.1> requires should not be incurred for well-characterized, commonly used materials for most dosage forms, especially when extractables and leachables will be a separate consideration. Alternatively, if you fully expect that the product will be part of your companies marketing program beyond 2025, or represents a high-risk use-case, perhaps with uncharacterized materials, then submitting the container system to USP <661.1> today may prove to be a cost savings strategy in the long run. As the pending chapters require compliance by 2025, the need for the testing will not go away. Additionally, industry can fully expect that the cost of USP <661.1> will only be higher in the next 2-4 years. In capital markets, prices for unique services tend to go up, not down.

We are hopeful that the overview information provided sets a basic foundation of understanding for the reader and addresses some initial points to consider when determining the ideal test method for your specific plastic container system. Like you, we wish the prescribed direction were simple and clear. In subsequent articles we will address more specific comparison points between the <661>, <661.1>, and <661.2> testing and begin to address other critical elements for consideration. The ultimate goal is to help you make the most appropriate and informed decision when it comes to your container qualification testing needs.